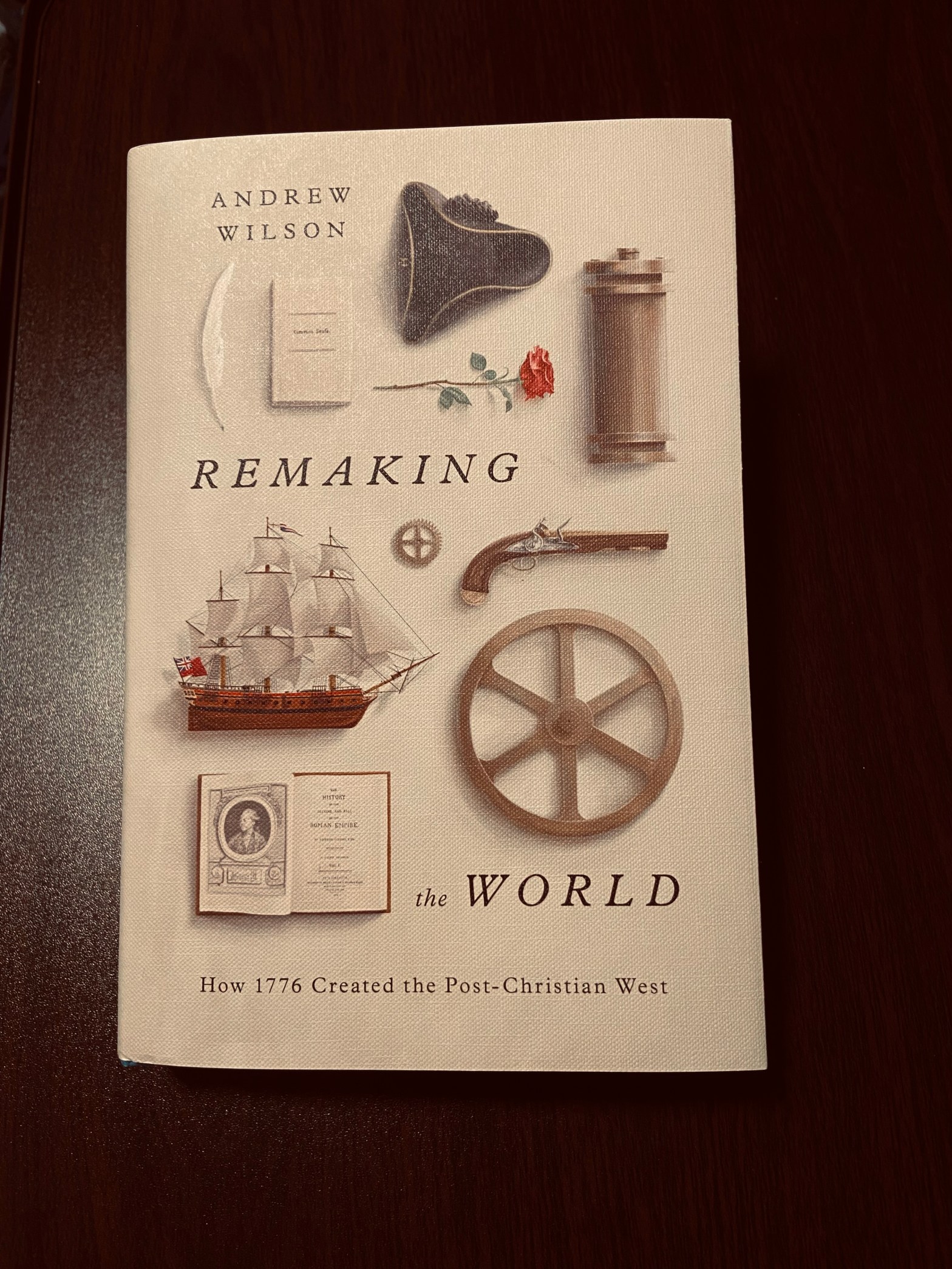

After reading Andrew Wilson’s new book “Remaking the World: How 1776 Created the Post-Christian West” I struggled to take stock of the many false notions, prejudices, and half-truths I have believed for most of my adult life about the rise of Western Civilization. Wilson, a teaching pastor at King’s College London, offers a well-researched, engaging volume of history deliberately focused around the year 1776 that includes 52 pages of bibliography and endnotes. Wilson traces seven major developments happening in 1776 and how they grew to make the world we know today. Among the many highlights in the book is his take on the dark ages.

Dark Ages

In Remaking the World, to no one’s surprise, we read how 18th-century philosophers regarded the medieval period between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance as dark and barbaric. Wilson comments, “ ‘the dark ages’: a thousand years of stultifying grimness in which people spent all their time burning witches, eating turnips, and dying of the plague, until early modern Europeans arrived and switched on the lights.”[1]

“Why…did the West slumber through a thousand years of darkness until Columbus and Copernicus and their contemporaries rediscovered the work done in Alexandria?”[2]

Carl Sagan

As a youth, I assumed the truth of this cliché. But it cemented itself in my mind as I and several million others gazed at the public TV series Cosmos. Author and scientist Carl Sagan famously lamented, “Why…did the West slumber through a thousand years of darkness until Columbus and Copernicus and their contemporaries rediscovered the work done in Alexandria?”[2] Like many others before and since, Sagan believed a thousand-year reign of religiously-motivated ignorance ended as Reason flowered in the Renaissance and triumphed during the scientific revolution.

But as Wilson explains, the dark ages idea was promoted much earlier for different reasons —by Protestants. Wilson observes that the dark ages story was “originally a Protestant account, with Roman Catholics held responsible for keeping us all in the dark for so long.”[3] To express his anti-Catholic sentiment, an Anglican wrote the ‘midle age’ was covered with ‘thicke fogges of ignorance’, in 1605—the same year as the Gunpowder Plot, a failed Catholic attempt to assassinate King James I and Parliament. Britons celebrate the coup’s failure each year on Guy Fawkes Day.

Wilson remarks that later the dark ages story “had morphed into an agnostic or even anti-Christian polemic”[4] by leading philosophers of the movement now known as the Enlightenment. Though neither one was light in the physical sense, the likes of David Hume and Edward Gibbon lent the considerable weight of their intellectual credentials to the “dark ages” story, emphasizing the difference between the light of their generation and the dark, foolish ignorance of superstition and religion.

The dark ages are familiar to us today in this sense, by which some outspoken atheists want to characterize all religious belief as ignorant and backward. The old science vs. religion canard still thrives on the widespread assumption that the dark ages story is true.

The old science vs. religion canard still thrives on the widespread assumption that the dark ages story is true.

Whether “anti-Christian polemic” of Enlightenment philosophers or Protestant fervor against Catholics gave rise to the dark ages story, it’s a far too simplistic formula to give us a true view of history. Elements of the story are so well known—the basic form of the narrative appears in some textbooks—that it’s not a stretch to say a majority of Americans hold mistaken assumptions about religion and science because of it. These assumptions exemplify what C.S. Lewis called chronological snobbery, because as Lewis observed, “Every age has its own outlook. It is especially good at seeing certain truths and especially liable to make certain mistakes.” The remedy, Lewis suggested, is to read old books. Despite the modern tendency to deny the relevance of history, we should realize that, because it influences the way we think, history is a part of who we are.

Progress?

If we decide to ignore Lewis’s advice to read old books, our natural tendency will be to compare our present age with those that came before. And ages past will suffer for the comparison. In our time, we are progressive, advanced, technological, industrial, smart, prosperous, and so on. Former times were backward, bigoted, benighted, even barbaric. We can obtain a more accurate view only if we “keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds,” as Lewis warned.

But even the word “backward” (or conversely the word “progressive”) implies a way of looking at history that is itself a legacy of the Christian West. As Wilson emphasizes, modern interpreters of history are themselves constantly viewing events in terms of progress or regress. And I would add, some high-profile adherents to secular humanism and scientism seem to think that even if the history of moral progress has not always been smooth, it trends in a positive direction (e.g., Enlightenment Now and The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker, or The Moral Arc by Michael Shermer). But dear reader, it ain’t necessarily so.

Modern, Western people have become accustomed to viewing history in a Christian way, that is, from a linear perspective, but many of us have substituted the true Christian telos of history for a creative range of new ends. At the same time, we don’t acknowledge our assumption that history is linear, nor do we admit that it has Christian roots. Consider, for example, Barack Obama’s “wrong side of history” comments,[5] the popularity of which indicates the near-universal acceptance of such a view. We are wiser, more advanced than our forebears. Progress is inevitable.

Modern people… zealously defend moral imperatives that grew out of the Christian worldview while denying, or remaining ignorant of, their Christian origins.

Throughout the book, Wilson reminds us that no one can completely escape the post-Christian assumptions implicit in this thoroughly modern world. Modern people, whether nominal Christians, atheists, pagans, radical progressives, or “nones”, will zealously defend moral imperatives that grew out of the Christian worldview while denying, or remaining ignorant of, their Christian origins. Those things we take for granted in the West (universal human rights, the abolition of slavery, racial equality, women’s rights, and so on) are indeed markers of true moral progress and are the legacy of centuries of Christian influence.

[1] Andrew Wilson, Remaking the World: How 1776 Created the Post-Christian West (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2023), 103.

[2] Carl Sagan, Cosmos (New York: Random House, 1980), 335.

[3] Wilson, Remaking the World, 103.

[4] Ibid.

[5] See, for example, David A. Graham, “The Wrong Side of ‘the Right Side of History’,” Atlantic, December 21, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/12/obama-right-side-of-history/420462/.