You may have heard the quote, “the most dangerous ideas in a society are not the ones that are being argued, but the ones that are assumed.” This clever aphorism is widely attributed to C.S. Lewis. But actually, Hollywood screenwriter and Christian believer Brian Godawa wrote this to paraphrase Lewis’s idea.1

Often, people fall prey to a commonplace assumption: the idea that people today have a more enlightened moral sense than people did in the past. If you doubt this, consider how quickly you meet with furrowed brows and indignant stares from your contemporaries when you voice a politically incorrect opinion.

Brett Kunkle and John Stonestreet observe, “Smugly, we think ourselves immune to the great evils of the past, confident we see more clearly than our morally unenlightened ancestors, as if we have no blind spots of our own. However, any illusion of moral superiority over those who lived before us is what C.S. Lewis aptly labeled ‘chronological snobbery.’”2

Chronological Snobbery…

is “the uncritical acceptance of the intellectual climate of our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of date is on that count discredited.”3 Here, the key word is uncritical. Instead of actually thinking about and studying the past, chronological snobbery encourages people to believe the current ways of thinking are right and superior, to the wrong and inferior ideas that came before. Thoughtful observers will realize this can’t possibly be true—every time period in history has had highs and lows. It is undeniable that many good things have come as the result of the pursuit of progress. But, as an illusion, chronological snobbery gives us the false confidence that now we know what is good better than anyone in the past.

Currents of thought that flowed in the 17th and 18th centuries, later known as the Enlightenment, encouraged people to envision a world in which belief in God was unnecessary. This shift in thought, coupled with the ever-increasing frequency of discoveries in science, led subsequent thinkers to slander religious belief as mere “ignorance and superstition”4 that should be left in the past. The concept of Progress was birthed, and Western civilization has never lost hold of the ideal. We think things are getting better all the time, in no small part because of the many breathtaking advances in engineering, science, and technology. No wonder we are prone to some degree of chronological snobbery, albeit unjustified.

Nobody likes a snob, because snobs think they are superior to others. Chronological snobbery is a bit different: you are tempted to join the other snobs and make yourself feel superior by disparaging truths of the past, even truths that were widely acknowledged. If you give in to this temptation, you’ll make new friends by proving you are aligned with current moral orthodoxy. You might even say that chronological snobbery has become fashionable. Ironically, we all know what happens to fashions.

Like Trotsky in Stalin’s Russia, they become unfashionable, hated, and dead. To participate in chronological snobbery is to take cheap shots at recently-unpopular ideas because of social pressure, not to evaluate the specific merits of those ideas.

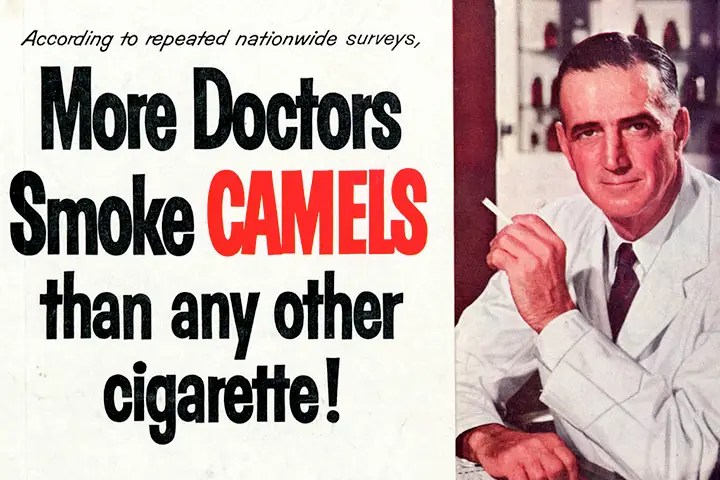

We know that smoking causes cancer, but did you know that decades ago, doctors sometimes recommended smoking cigarettes?5

And isn’t that hilarious? When the laughs fade, ask why it sounds funny to us. We’re laughing (snobbishly) at people in the past who were ignorant of the danger. I’ll guess that none of us did the painstaking research to prove the causal links between smoking and cancer. We received this valuable information secondhand, simply by drawing breath sometime in the last 4 or 5 decades. Do we honestly think ourselves so superior?

The study of history should engender humility, not arrogance. “Take my instruction instead of silver, and knowledge rather than choice gold, for wisdom is better than jewels, and all that you may desire cannot compare with her…Buy truth, and do not sell it; buy wisdom, instruction, and understanding.” (Proverbs 8:10-11; 23-23)

If we don’t think carefully, we will take for granted the assumptions of contemporary culture. And if we expend no effort to seek the truth, eventually we will accept everything the world tells us. In fact, this is the easiest thing we can do—because

no effort is required to accept

everything contemporary culture

tells us about the past.

By contrast, Christians have a higher duty: to seek the truth, and never let it go.

Christians in every generation can guard against excesses of the current age through the study of history. When he opined about chronological snobbery, Lewis intended that we should refresh our thinking with ideas from the past: “The only palliative is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds and this can only be done by reading old books.”6 Undeniably, human life is far better now in many quantifiable ways than it was a hundred years ago: lower infant mortality, mass electrical power, increased access to clean water, and many childhood diseases eradicated. We can also point to moral advances: women’s rights, human rights, abolition of slavery, child labor laws, and many other goods.

These wonderful things came to be, in no small part because of the consciences of individual Christians who sought to create a better situation for their fellows. These were not “chronological snobs,” but people of courage who thought differently, sought truth, and had “understanding of the times” (cf. 1 Chronicles 12:32). And as C.S. Lewis reminds us, “all discoveries are made and all errors corrected by those who ignore the ‘climate of opinion’.”7

Don’t be a snob. Be a student of history. As Jesus-followers, Christians should reject the allure of what is fashionable, and seek truth instead. The truth endures, and ultimately, the truth will not be denied.

1 Brian Godawa, “Postmodern Movies: The Good, the Bad, and the Relative, Part I,” SCP Newsletter, 23:3 (Spring 1999): 11, accessed July 3, 2023, http://web.archive.org/web/19991012175804/http://scpinc.org/cgi-bin/index.cgi.

2 John Stonestreet and Brett Kunkle, A Practical Guide to Culture: Helping the Next Generation Navigate Today’s World (Colorado Springs, CO: David C. Cook, 2017), 28.

3 C.S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy (New York: Harper Collins, 1955), 254.

4 Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (New York: Penguin Random House, 2018), 10.

5 Simon Barley, “When Cigarettes Were Acceptable” British Medical Journal, 322, no. 7280 (2001), 203.

6 C.S. Lewis, God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1970), 202.

7 C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain, in The Complete C.S. Lewis Signature Classics (New York: Harper Collins, 2002), 631-632.